February 10, 2004

Koreans Look to China, Seeing a Market and a Monster

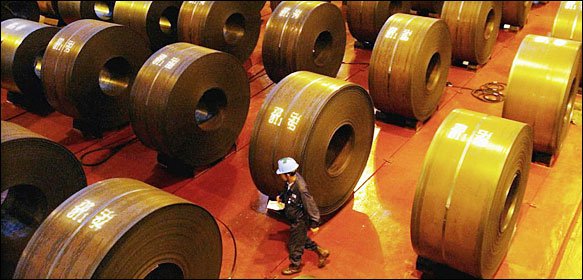

Rolls of steel at a Posco mill in Pohang await shipment. Last year, South

Korea's steel exports to China jumped 60 percent, while shipments to the

United States fell 27 percent.

![]() EOUL, South Korea - After a century of

looking east, first to Japan and then to the United States, Korean

business leaders are now gazing west, to China. But it is a fascination

tinged with fear.

EOUL, South Korea - After a century of

looking east, first to Japan and then to the United States, Korean

business leaders are now gazing west, to China. But it is a fascination

tinged with fear.

In 2003, nearly half of South Korea's foreign investment went to China, and its exports to China jumped 50 percent. Winging west over the 250-mile-wide Yellow Sea, China-bound flights are filled with business executives bearing deals intended to ensure that China replaces the United States as South Korea's major economic partner.

Samsung Electronics announced that it would make China the main base for production of its personal computers and flat screens. Hyundai Motor, the nation's biggest carmaker, and Kia Motors, a subsidiary, announced plans to make a million cars a year in China by 2007.

But as South Korea's blue-chip companies funnel new investment into China, economists here worry that South Korea's economic sparkle - "the miracle on the Han River" - will lose its luster. With Northeast Asia's foreign investment river diverted to China, economic growth here fell by half in 2003, to 3 percent.

As China's low-wage workers churn out millions of cars, computers and cellphones, its exports seem destined to look like South Korea's. As Korean companies move research and development units to China, surveys indicate that China's technological lag behind South Korea is three to five years, and shrinking.

"China's rapid ascension to the global economic stage has forced Korea to accept the painful yet glaring truth that its competitive edge is steadily slipping away," Kim Wan Soon, the Korean government's investment ombudsman, wrote in a recent newspaper essay. "An increasing number of capital-intensive Korean firms are positioning themselves to assemble high-tech components in China."

In South Korea's world-renowned heavy industries, notably steel and shipbuilding, planned investment in China will one day make for head-to-head competition.

"China is challenging Korea in heavy industries more than ever," Andy Xie, Asia economist for Morgan Stanley, wrote in a recent report. "China is repeating Korea's model of 'low price but high volume' on a vast scale. Korea is likely to suffer ever more losses in its heavy industries."

In the short term, Korea's heavy industries are booming, riding the tide of China's rise.

China, the world's largest steel importer, lies one day by ship from South Korea, the world's No. 5 steel-making nation. Last year, South Korea's steel exports to China jumped 60 percent, while to the United States they fell 27 percent. Korea exported to China more than four times the steel it sent to the United States.

Posco, a unit of Pohang Iron and Steel and South Korea's largest steel maker, is investing $800 million in China.

But for the moment, China's growth is causing all boats to rise in South Korea, the world's largest shipbuilder.

Last year, China's oil imports grew about 30 percent, and container traffic at China's seven largest ports grew 40 percent. This contributed to a doubling of ship orders placed last year with South Korea's shipbuilders. Of 470 orders, 43 percent were for container ships and 22 percent were for tankers.

But South Korea's Hyundai Heavy Industries may lose its title as owner of the world's largest shipyard. The China State Shipbuilding Corporation recently broke ground on what the company said would be the world's largest shipyard.

While no one knows what Asia's economic world will look like a decade from now, South Korean business executives take China's continued rise as an article of faith. With economists forecasting 5 percent growth for South Korea's economy in 2004, the reason most often cited is expanding exports to China.

Last year, South Korean businesses invested $2.5 billion in China, compared with only $50 million in Japan. Feeding their interest, Korean business newspapers now maintain regular economic pages devoted solely to Chinese news. With Korean companies signing deals in China in 2003 at the rate of 12 a day, 22,000 of them now have investments in China, employing about one million Chinese workers, according to the Korea International Trade Association. Investments range from workshops in Northeast China's ethnic Korean enclave, to a project by Korea Electric Power, the nation's largest power company, to build two coal-fired plants in Henan Province.

Bilateral trade is expected to double in five years, to $100 billion. In 1992, it was only $6.2 billion. Determined to win market share, Samsung and LG Electronics, Korea's largest consumer electronics companies, have each set goals of selling $10 billion worth of products in China by 2005. To compete with China in the long run, economists say, South Korea must either extend its low-wage, high-volume manufacturing model to North Korea, or open its economy.

China's monthly average industrial wage is $111, compared with $1,524 in South Korea. Factory land costs far less in China than in South Korea, where 40 million people are crowded into an area the size of Massachusetts. Not surprisingly, manufacturing accounted for 91 percent of Korean investment in China last year.

One way out would be to marry South Korea's capital and technological expertise with North Korea's low-wage labor. In a first step, a South Korean industrial park is under construction north of here, just inside North Korea. The park, which might open in 2005, is to hold about 700 South Korean factories.

But in a Communist country where allowing people to fix bicycles for pay is considered a major economic reform, North Korea's inertia is an obstacle to the fast development of partnership projects. In addition, North Korea's nuclear weapons program leaves the nation exposed to economic sanctions by Japan, the European Union and the United States.

The other route would be to break down barriers and open South Korea to more foreign investment.

Last year, South Korea received only $6.5 billion in foreign investment, down from $15 billion in 2000. Last year, South Korean companies invested $5.4 billion overseas. This year, South Korea may cross into the category of net foreign investor.

To arrest this trend, projects are under way to create investor-friendly special economic zones, largely around the port of Inchon.

"That is not enough," Mr. Xie wrote, arguing for exposing South Korea's large "chaebol" conglomerates to more competition. "The right vision is to turn the whole country'' into such a zone.